NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) is seeking to increase the diversity of study type and design submitted for funding. This case study outlines a novel research design for optimising diagnosis of symptomatic cancer.

Programme details

Researcher name: Professor William Hamilton

Organisation: NHS Bristol Clinical Commissioning Group

Funding: £1.9m, 2010 - 2016

Aims of the programme

In 2007, around 5000 lives a year were lost in the UK compared to sister countries from later cancer diagnosis. The Optimising diagnosis of symptomatic cancer programme sought to improve the time to diagnosis of symptomatic cancers focusing, although not exclusively, on lung, colorectal and pancreatic cancer.

Three thematic and synergistic areas were targeted:

- SYMPTOM - an investigation of symptoms that prompt patients to seek healthcare, in order to identify symptoms associated with delays before presentation to healthcare.

- CAPER - an identification of the symptom risk profiles for a wide range of cancers, where the importance of different symptoms is not known i.e. delays in the GP consulting room

- PIVOT - the design of new cancer diagnostic pathways driven by patient views

Programme design

Factors influencing patient appraisal of symptoms and associations with cancer diagnosis

This comprised three parallel cohort studies of all patients from general practices referred for symptoms suggestive of lung, colorectal and pancreatic cancer. Each study had a nested in-depth qualitative interview study using a purposive sample of those diagnosed with and without cancer.

Quantifying the risk of cancer and diagnostic actions

The aim was to conduct 6-8 new matched, case-control studies using data from the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) to find statistically and clinically significant pre-presentational features (symptoms). Ultimately 14 sites were studied, because the researchers were able to semi-automate the processes. The GPRD data would also be interrogated to carry out studies of existing main routes patients took to diagnosis, and will explain why so relatively few patients take the standard route via 2-week wait referral from primary care.

Consumer values in the design of cancer investigation services

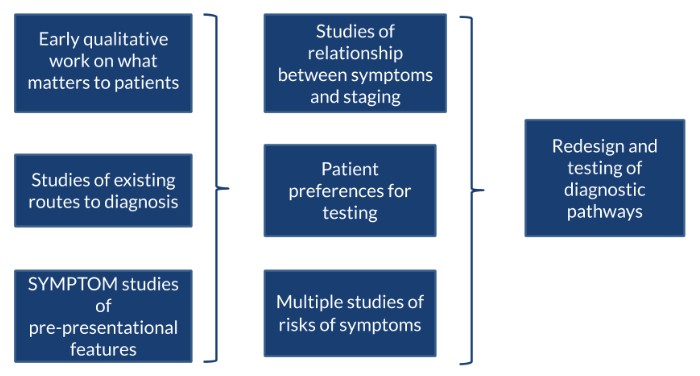

This had four components, which are described in this text and the diagram below. The researchers conducted an early in-depth qualitative interview study with patients who had undergone cancer investigation, to identify what factors mattered most to patients. Using this, they undertook a large vignette study that sought to find patient preference for testing and designed multiple studies relating to levels of disease risk of symptoms for the three exemplar cancers.

The researchers added two studies using Bayesian methods to establish the relationship between cancer symptoms experienced and cancer staging at diagnosis. This helped to model the most effective investigative pathway for patients presenting to GPs with symptoms that could trigger further investigations for cancer.

The study concluded with a workstream to redesign and test the diagnostic pathways using the information generated by the earlier parts of the programme.

Why was this programme design chosen?

An interrelated mixed methods programme of work was needed to be able to analyse the complex interplay of human and medical factors. Crucially, this had to be patient-driven, in discovering what matters to patients and their appetite for cancer testing – even if the actual chance of cancer was small. The programme did not include a final trial, as there were simply too many unknowns at the outset to make a realistic trial appropriate.

Summary of findings

The SYMPTOM study found a number of 'alarm' symptoms that were key to delays in cancer diagnosis but rarely reported as a first symptom, or as a symptom at all. These included haemoptysis, rectal bleeding and jaundice. Co-morbid conditions, like depression, could mask new or changing symptoms for both people and their GPs. GP safety netting and tracking potential cancer symptoms was found to be central to appropriate referral.

To help GPs identify cancer more quickly, the team produced a series (16 at the last count) of evidence based risk assessment tools (RATS) that showed the positive predictive value for a cancer diagnosis of individual and pairs of symptoms in an accessible way. In the first phase the RATS for lung and colorectal were made available to all practices in England as computer mouse mats.

Subsequently, the team converted the algorithms into electronic software, which auto-searches the GP records for patients with possible cancer, and alerts the GPs to the possibility. A broad range of cancers are now covered including bladder, kidney, oesophago-gastric, pancreatic, uterus, ovarian and prostate cancers. These are being trialled in over 500 practices, beginning in 2019.

The patient survey found a clear preference for investigation at levels of risk as low as 1%; lower than NICE guidance at the time of the research which was approximately 5%.

What has happened as a result?

The NICE Guideline ‘Suspected Cancer: recognition and referral’ (NG12), which governs approximately £1bn of annual NHS spending has been very strongly influenced by this body of work, with William Hamilton being the clinical lead for the revision of this guidance. Of the 176 recommendations, approximately 30 are directly related to one of the RATs papers. Most significantly the PIVOT study resulted in the likelihood of cancer diagnosis threshold for referrals to be reduced from 5% to 3%.

The proportion of cancers diagnosed as an emergency is falling by approximately 1% each year (saving approximately 15,000 lives over the last 5 years), and the time to diagnosis with a symptom is falling. Cancer survival is improving, and finally the gap between the UK and its sister countries is narrowing. These advances can be attributed in part to the team’s diagnostic research work.